|

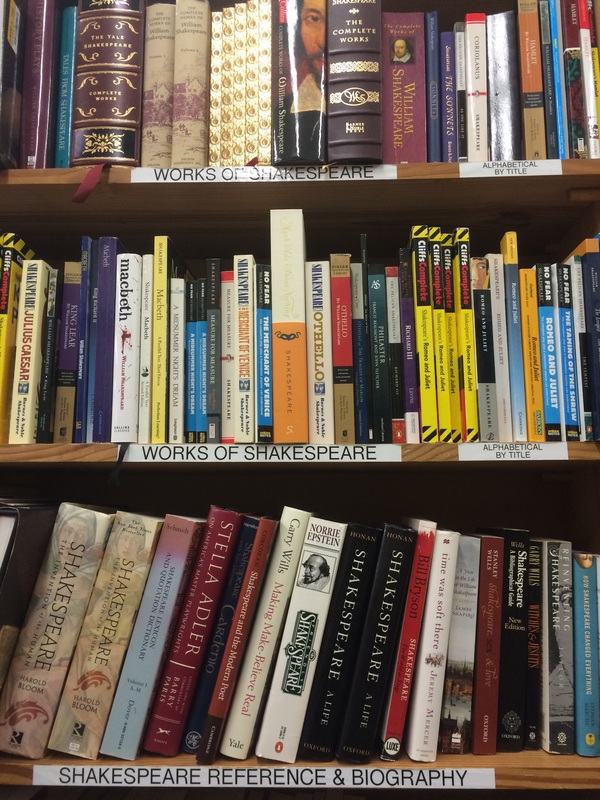

6/16/2015 2 Comments OMG! WTF! BBQ!I know, I know, the new OMG Shakespeare series from Penguin Random House symbolizes the “nadir of Western civilization” in its translation of several works of the Bard into an exchange of text messages, complete with abrvtd txt spk and emoji. It’s an “absolute atrocity to written literature” and “the most disgusting thing [one has] ever seen.” Or at least the 1-star reviews on Amazon (from reviewers who don’t actually provide any evidence of having read the books) suggest it is. And no, I haven't read them yet either. That's why I'm discussing them in a blog post and not leaving an Amazon review. I'm also not pretending to be talking about the execution; it's the concept this post is about, as most of the online discussion I've seen has been. I’m not on the cutting edge of internet slang myself. I’m such a nerd, I even text with full words and complete sentences. Whenever I use a hashtag, I feel like a poser, and I don’t mean during my Barney Stinson impression—I mean when I’m actually sending a tweet. And yet I love the entire idea of this series, which includes srsly Hamlet, YOLO Juliet, A Midsummer Night #nofilter, and (my favorite title) Macbeth #killingit. While most of my friends’ reactions have ranged from confusion to despair, with a few giggles here and there, a couple of the dissenters and I have been ROFLMAO, as we quaintly used to say in 1994. A spirited defense First, I must stress that I don’t think this series is going to be read by kids or teenagers all that much. I don’t think very many people will be getting these books because they want to learn about Shakespeare, and those who need a substitute for the real thing will continue using Cliff’s Notes like their foreparents and SparkNotes like their foresiblings. I think that much of the concern and dislike and five-poop-emoji ratings this series has earned has come from a fear that the series is intended to give the playwright wider appeal and to talk to “the kids” in a language they understand. The books are even published under the Random House Books for Young Readers imprint (italics mine), and some well-meaning supporters on social media try to argue, “But it will expose Shakespeare to people who wouldn’t otherwise read him!” and think the people they’re saying it to will see this as a good thing. There are two groups who I believe are going to love these (or the idea of these—again, I can't personally vouch for whether they're actually funny or a good reflection of the narratives yet) in particular. One group, which I count myself a part of, consists of Shakespeare fans with a satirical sense of humor. The other group is Shakespeare haters with a cultured sense of humor. In other words, they’re people who have already read and/or seen these plays and have an opinion about them. There is a third group, probably smaller, probably less appreciative, but of the same age group, who read the books in high school but didn’t understand them and will use this series to fill in the gaps. Even if this three-part audience isn’t the one Penguin Random House had in mind, it’s the one I expect they’ll end up with. The first of these groups know these plays from front to back and will laugh, cry, and snort to see their favorite lines transformed into pixel pictures. The second group slogged their way through them in high school and are excited that the sadistic English teacher who subjected them to that torture is now getting her comeuppance. The third, of course, will say, "Oh that's what he was trying to say. Why didn't he just say that?" Some of the people in these three groups might even be teenagers right now and will enjoy it on multiple levels because what Horatio is texting to Hamlet looks a whole lot like something they wrote to their bff earlier. But the key thing is that they are enjoying the books not outside the context of or instead of the original material but entirely in reference to it. Imagine for a moment what this would look like if a comedy troupe like the Reduced Shakespeare Company had gotten to it first. Reed Martin and Austin Tichenor stand on opposite sides of a stage in costumes apparently pilfered from a community theatre closet. Each has a phone in his hands and is tapping letters while reading out loud, “Dude. It’s 9 a.m. Wake up! Angry face.” “Sad face. Ugh, that’s it? I don’t wanna. I’m too depressed. I have nothing to live for. Really sad face.” “Oh crap. Poop emoji.” Funny, right? Unlikely to signal the deterioration of literacy, right? It’s the same text, so what makes it different? Come up with answers for that if you want, but I’m going to move on to… What I love about itShakespeare* has been modernized every way imaginable. A friend in a Facebook thread mentioned the graphic novelization of the plays. It has been made into or been the inspiration for musical theatre, animation, teen dramas, teen comedies, not-so-teen comedies, and sci fi.** Why draw the line? In particular, why draw the line at text speak? How is that not arbitrary? Converting the plays into text messages is particularly brilliant because what are text messages but a written form of dialogue? This is actually the form that a play—particularly a Shakespeare play, with its well-known dearth of stage directions—could most easily take if converted to a modern means of communication. Alternatively, what if you took all the recent text messages in your phone and those of your social circle and organized them into something meaningful? The result might not be as dramatic as a Shakespeare play (shipwrecks, parental ghost sightings, and throne swapping don’t take place every day, you know), but the format would already be there. The differences between theatre and texting underline the cleverness of this move even more firmly. The dialogue in a play implies proximity, nearness, not just between the characters but between the actors and the audience. As we all recognize at stray moments right before we look back down at our devices, texting both brings us closer—makes us more available to one another—and divides us, as it renders moot the need to be face to face or to hear each other’s voices as we do so. The image of teenagers thumbing away at the dinner table until their parents’ rebukes grow loud enough to cut through the zone is not only recognizable but cliché. OMG Shakespeare is neither the first nor the last media product to highlight this transformation in how we communicate, but it’s a particularly witty one. Critically reclaimedA couple of months ago, a designer named Joe Hale translated the entire text of Alice in Wonderland into emojis. He’s done the same with Peter Pan. Each product is both a fascinating piece of art (he sells them not as books but as posters) and a treatment of Emoji*** as a visual language unto itself.

I don’t speak Emoji; I’ve had a smartphone for three years but only found where the emoji are hiding a few weeks ago. I would need to use the original text as a Hale-to-Carroll dictionary to get through even a sentence of this translation. While that might just mean that I’m slow to catch up with this stuff, it also means that Emoji isn’t strictly a pictorial version of English, though its grammar is probably closely aligned in Hale’s representation. The translated snippets offered in the Huffington Post’s coverage of Hale’s Wonderland offer a sense of how the language is constructed and how a reader could learn to catch on with enough concentration. “With” is depicted with a pair of dancing girls. “Without” pairs the girls with another person crossing her arms in front of her face. Plural is signified by multiple iterations of the same emoji. And then there’s Alice, represented by a blonde head with a crown. She doesn’t get a name, but the consistent use of the same icon for her indicates her as the text’s central heroine. Languages of the world vary in complexity, so the relative simplicity of Emoji isn’t unique. It’s not unique in its constructed nature, either, as a few people could probably tell you in Klingon or Esperanto. At the moment, it's doubtful anyone besides Hale is treating Emoji as a fully fleshed-out language, and it certainly doesn’t have universally accepted rules for what icons represent what concepts, but there are doubtless many others using their own variations of it each time they turn on their phones. Hale’s translations suggest that although these modern hieroglyphics don’t yet constitute a shared form of communication in all its sophistication, the potential is there if it were needed or wanted. The OMG Shakespeare series isn’t written entirely in Emoji, but if we understand emoji as linguistic symbols that convey meaning among those who share a comprehension of them, why not understand verbal text speak the same way? Sure, it’s a simplification of English, and sure, it promotes irritating habits that some young people need to learn not to transfer into emails with professors or employers (or anyone else they hope will take them seriously), but why not recognize its centrality in modern communication? Ultimately, OMG Shakespeare is funny to some of us for the same reason it bugs the heck out of others: it takes texts that many consider the epitome of written English, crosses them with texts (literally—texts) that many consider the lowest form of written English, and unapologetically hybridizes them. Some will find this frightening. Some will find it disconcerting. I find it clever as 💩. * You might notice that I treat “Shakespeare” here less as a guy than as a phenomenon, a genre, a concept, and a category of work. I’m sorry, Will, but for the purpose of this post (as for most discussion of this series elsewhere), you won’t be a “he” but an “it.” ** If you don't want to click through, those are West Side Story, Lion King, O, 10 Things I Hate About You, Strange Brew, and Forbidden Planet. *** I am capitalizing it where I use it as the name of a language and leaving it lowercase when referring to the icons.

2 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

March 2017

CategoriesAuthorI'm Lea, a freelance editor who specializes in academic and nonfiction materials. More info about my services is available throughout this site. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed