|

In the midst of Donald Trump’s controversial nominations to cabinet positions, one particular appointment of more moderate profile came to the public’s attention for other than the usual reasons. Monica Crowley, formerly of Fox News and the Washington Times, was selected in December to serve as senior director of strategic communications for the National Security Council. Beginning on January 9, sources (including Politico Magazine and CNN Money) reported on Crowley’s past writings, revealing unambiguously that she had plagiarized large portions of her 2000 dissertation for Columbia University. By January 16, Crowley had withdrawn from consideration for the NSC post. The plagiarism took the form of enormous passages from published books showing up at intervals throughout the dissertation. The most interesting thing to me in Andrew Kaczynski et al.'s CNN piece is that “Crowley cited these . . . sources in footnotes at various points in her dissertation, but often failed to include citations or to properly cite sources in sections where she copied their wording verbatim or closely paraphrased it.” As Alex Caton and Grace Watkins of Policito put it, “Parts of Crowley’s dissertation appear to violate Columbia’s definition of ‘Unintentional Plagiarism’ for ‘failure to “quote” or block quote author’s exact words, even if documented,’” while other passages appear much more to have been intentionally copied verbatim without attribution at all (para. 7).

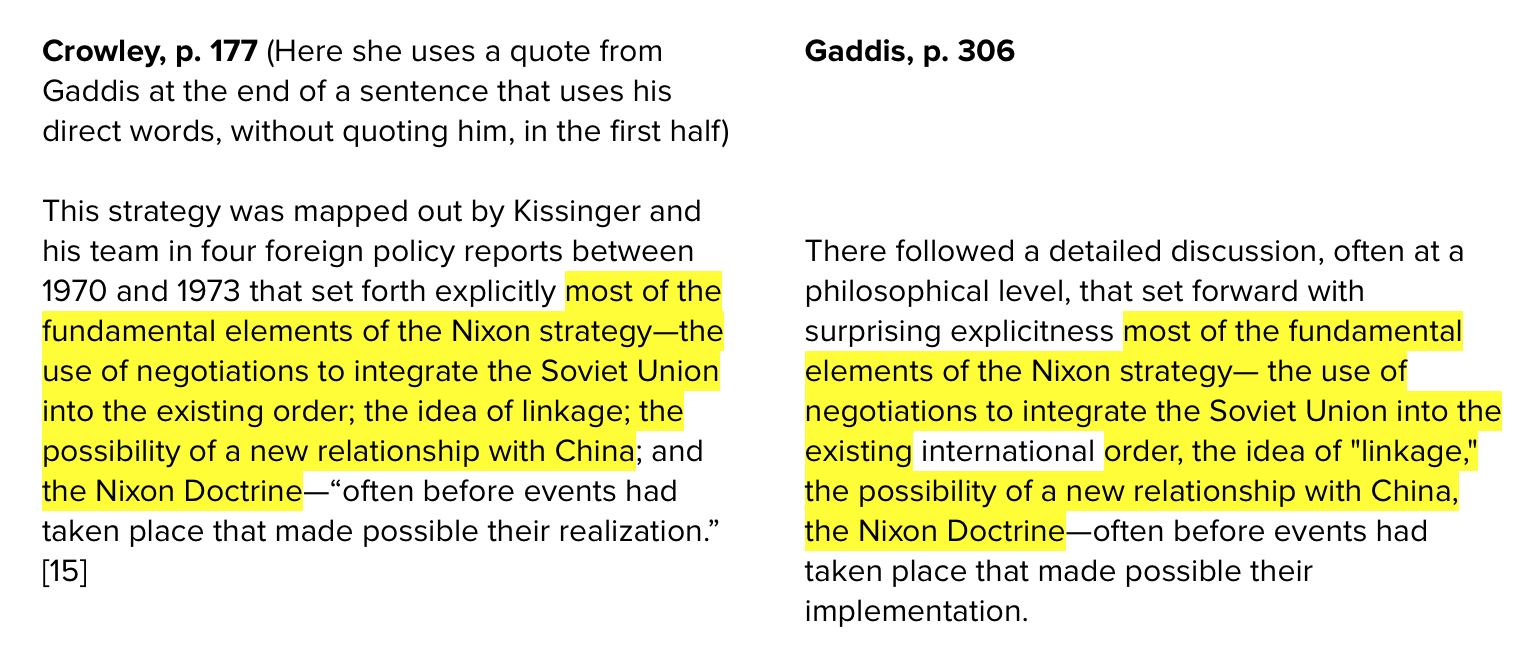

But here’s the thing. Everyone knows plagiarism is wrong. But I believe a lot of people — whether or not Monica Crowley is among them — don’t know when they’re plagiarizing. There are reasons Columbia's policies recognize "Unintentional Plagiarism": because (1) it happens and (2) regardless of intent, it's still plagiarism. All students at all levels of education are responsible for knowing what plagiarism is. There seem to be, however, some areas of either haziness (in students’ understanding of the rules) or laziness (in their application of them). And academic integrity is just about the only aspect of writing a dissertation or thesis in which being hazy or lazy can irreparably threaten your degree and your future career. There are a lot of things you can finish grad school not knowing, but how to write without plagiarizing should never be one of them. (Or to unravel that ugly triple negative, you need to know how to write without plagiarizing.) To lay it all out as starkly as possible, your dissertation drafts can be poorly written, poorly organized, and poorly spelled, with terrible grammar, messy punctuation, and weak research, and it still won’t necessarily mean the end of your career. It will mean you’ll spend a lot more time on revisions; it could mean you’ll have to pay an editor to get the language in shape; it might mean you’ll run out of funding in the process (if applicable); and if you happen to turn that mess in for your defense, it will mean that you’ll have an embarrassing time of it with excruciating feedback and a call for enormous changes. But there can still be hope for you and that awful paper, as long as all the quotes and ideas presented in the document are correctly and appropriately attributed. That’s right. The only mistake you can make that will be a complete and utter dealbreaker (as opposed to a frustrating setback) is not attributing your sources correctly. All other mistakes are forgivable and fixable. This one, not so much. That should be a pretty low barre, right? I mean, the citations don’t even have to be formatted well to avoid losing your chance at your degree. They just have to be there. Those and everything else that’s wrong with it can be corrected with enough blood, sweat, and tears. And time and possibly money. But turn in a paper with incomplete attributions, and all those resources and bodily fluids will have been a waste of your time. So given that attribution errors are the only problem so critical that they can ruin your career in one deadly stroke, why do they even happen? How is it that any writer would devote less attention to citations than to any other aspect of their work? I really do think that in most cases it’s ignorance, and sometimes it’s apathy. The Crowley coverage can help. Both CNN and Politico offer side-by-side comparisons of Crowley’s plagiarized content and the sources it came from. Crowley wrote her dissertation before plagiarism detection software had become commonly available and widely used, so she might not have expected the paper would ever be scrutinized in quite this way (though it doesn’t explain her plagiarism in the 2012 book). Learning from Crowley's Example I: Mixing Correct and Incorrect AttributionThe comparison and comments in the Caton and Watkins piece show that her efforts at attribution are there, sort of, but are accompanied — sometimes in the same paragraph — by something improperly used or cited. Here’s an example: She had the presence of mind to quote the last part of the paragraph correctly, but it’s unclear why she wouldn’t have done so with the other thirty-seven words in this section. When I discover that a client has done something similar (which isn’t often because I only check text if it waves a red flag, and my only tool available is Google), I try to give them the benefit of the doubt. If you’ve ever committed this error or didn't realize there would be a problem with it, here’s my advice:

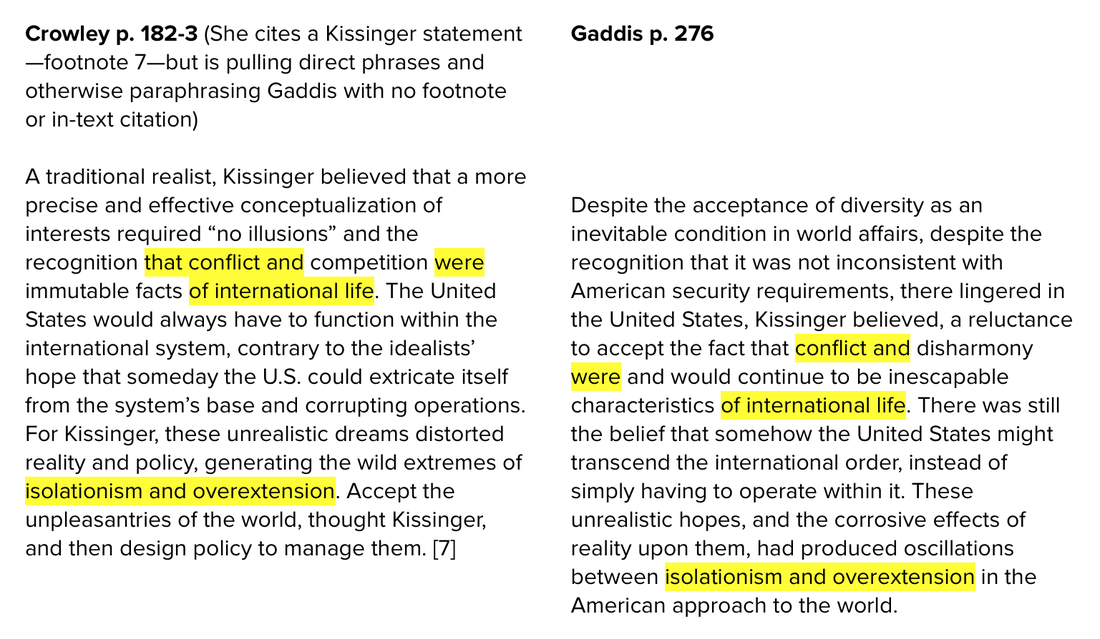

Learning from Crowley's Example II: The Perpetual Paraphrasing Problem and Word Count LogicTwo murky areas have to do with paraphrasing — when it's acceptable and when it's a problem — and the question of how much text from another source needs to be there before you have to put quotation marks around it. Back when I was teaching, students told me things like, “My high school English teacher said if it’s five words or more, it should be in quotes,” though it never seemed as though any two English teachers gave their students the same number of words. Let’s take a look at another excerpt from Crowley’s dissertation. The journalists appear to be using a computerized plagiarism checker, and computer programs don’t understand context, so three copied words in a row may or may not mean anything shady. But they call attention to the paragraphs, and it’s worth looking at their entire content, not just the parts that are highlighted. Many of the parts that are not identical are nonetheless simply swapped out — some with direct paraphrases and others with original phrases that nonetheless do little or nothing to alter the sentence structure. “Disharmony” became “competition,” “inescapable characteristics” became “immutable facts,” “unrealistic hopes” became “unrealistic dreams,” and “oscillations” became “wild extremes.” Meanwhile, “transcend the international order” became “extricate itself from the system’s base” while exchanging position with “having to operate within it” and “function within the international system.” There are two things to look at in the way Crowley treated her source material here that students and other writers should take to heart.

How Editors Can and Cannot Help with Citations and Attributiontl;dr: Editors can often help with citation formatting, but they aren't plagiarism detectors. Full explanation: In most cases, working with an editor on citations really just means the citations: formatting them and making sure they’re complete. You need to be aware of the policies that exist at the institutional, departmental, and program levels and your advisor’s requirements, along with what you and the editor agree that you will pay her for. Under normal circumstances, the editor will assume that all your quotes have quotation marks around them or are (or should be) put in block form. If you know you’re weak in any of those areas, you can communicate with your editor to figure out a way to highlight spots you need help formatting. In other words, you’re not trying to hide any quotes or passages that might not be presented correctly or hope they go unnoticed — you’re explicitly identifying them and asking for help with them. Those are the types of questions and considerations that apply to a “normal” paper with “normal” citation problems. With respect to more significant attribution errors, the main point that needs to be underlined is this: No one has responsibility for making sure your sources are correctly quoted and attributed but you. Your editor might spot problems, call them to your attention, and give you pointers for how to avoid the same mistakes in future drafts or chapters — but they also might not. Editors, like professors, are skilled readers who can sometimes see the variations in tone or voice that crop up in student papers and that raise red flags that some of the text might not be original to the student. But some of those variations are much more visible than others, and if the red flags don’t go up, editors aren’t going to intuitively know that you’ve done an oopsie with your attribution. Furthermore, even if they do locate and fix or query an oopsie — or seven, eight, twenty oopsies — it does not imply they will have found all of them. You, in such a case, need to learn from the comments the editor leaves concerning the found oopsies to correct the ones they didn’t spot. And to not make those mistakes again. Let’s say, for instance, you’re Monica Crowley, and you’ve hired a copyeditor who just happens to have just read one of the books you’ve used as a source. Let’s say this copyeditor recognizes the passages and leaves queries to you, saying, for instance, “Since I have the Christensen book on hand, I checked this passage against p. 248 and found that it’s a direct quote. I’ve enclosed this section of text in quotation marks and updated the footnote. Please do the same wherever else necessary.” The copyeditor has not read Gaddis, Larson, Oye, Milner, and the other authors you (Imaginary Crowley) have plagiarized and obviously hasn't memorized the entire Christensen book, either, so they haven’t made equivalent fixes or even queries. This doesn’t somehow mean that this one Christensen quote is the only one you shouldn’t plagiarize, and it doesn’t mean the editor has failed in their ability to spot problems. Rather, the fact that the copyeditor found even one instance is lucky for Imaginary Crowley because it means she should now know what else it’s necessary to go back to and fix. Crowley and other dissertation writers can’t rely on even that one fix happening. If it does, the writer should think of it as a bonus. Plagiarism of these kinds and others might get by the editor, and it might get by the committee. But if the dissertation gets pushed through plagiarism detection software, whether right away or 16 years down the line, it could mean the end of a career, or at least of all professional credibility. And all because a couple of quotation marks were just too much to type. ReferencesCaton, Alex, and Grace Watkins. 2017. "Trump Pick Monica Crowley Plagiarized Parts of her Ph.D. Dissertation." Politico, 9 January. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/01/monica-crowley-plagiarism-phd-dissertation-columbia-214612.

Kaczynski, Andrew, Chris Massie, and Nathan McDermott. 2017. "Trump Aide Monica Crowley Plagiarized Thousands of Words in Ph.D. Dissertation." CNN Money, 12 January. http://money.cnn.com/interactive/news/kfile-monica-crowley-dissertation-plagiarism/index.html.

5 Comments

|

Archives

March 2017

CategoriesAuthorI'm Lea, a freelance editor who specializes in academic and nonfiction materials. More info about my services is available throughout this site. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed