|

In the midst of Donald Trump’s controversial nominations to cabinet positions, one particular appointment of more moderate profile came to the public’s attention for other than the usual reasons. Monica Crowley, formerly of Fox News and the Washington Times, was selected in December to serve as senior director of strategic communications for the National Security Council. Beginning on January 9, sources (including Politico Magazine and CNN Money) reported on Crowley’s past writings, revealing unambiguously that she had plagiarized large portions of her 2000 dissertation for Columbia University. By January 16, Crowley had withdrawn from consideration for the NSC post. The plagiarism took the form of enormous passages from published books showing up at intervals throughout the dissertation. The most interesting thing to me in Andrew Kaczynski et al.'s CNN piece is that “Crowley cited these . . . sources in footnotes at various points in her dissertation, but often failed to include citations or to properly cite sources in sections where she copied their wording verbatim or closely paraphrased it.” As Alex Caton and Grace Watkins of Policito put it, “Parts of Crowley’s dissertation appear to violate Columbia’s definition of ‘Unintentional Plagiarism’ for ‘failure to “quote” or block quote author’s exact words, even if documented,’” while other passages appear much more to have been intentionally copied verbatim without attribution at all (para. 7).

But here’s the thing. Everyone knows plagiarism is wrong. But I believe a lot of people — whether or not Monica Crowley is among them — don’t know when they’re plagiarizing. There are reasons Columbia's policies recognize "Unintentional Plagiarism": because (1) it happens and (2) regardless of intent, it's still plagiarism. All students at all levels of education are responsible for knowing what plagiarism is. There seem to be, however, some areas of either haziness (in students’ understanding of the rules) or laziness (in their application of them). And academic integrity is just about the only aspect of writing a dissertation or thesis in which being hazy or lazy can irreparably threaten your degree and your future career. There are a lot of things you can finish grad school not knowing, but how to write without plagiarizing should never be one of them. (Or to unravel that ugly triple negative, you need to know how to write without plagiarizing.) To lay it all out as starkly as possible, your dissertation drafts can be poorly written, poorly organized, and poorly spelled, with terrible grammar, messy punctuation, and weak research, and it still won’t necessarily mean the end of your career. It will mean you’ll spend a lot more time on revisions; it could mean you’ll have to pay an editor to get the language in shape; it might mean you’ll run out of funding in the process (if applicable); and if you happen to turn that mess in for your defense, it will mean that you’ll have an embarrassing time of it with excruciating feedback and a call for enormous changes. But there can still be hope for you and that awful paper, as long as all the quotes and ideas presented in the document are correctly and appropriately attributed. That’s right. The only mistake you can make that will be a complete and utter dealbreaker (as opposed to a frustrating setback) is not attributing your sources correctly. All other mistakes are forgivable and fixable. This one, not so much. That should be a pretty low barre, right? I mean, the citations don’t even have to be formatted well to avoid losing your chance at your degree. They just have to be there. Those and everything else that’s wrong with it can be corrected with enough blood, sweat, and tears. And time and possibly money. But turn in a paper with incomplete attributions, and all those resources and bodily fluids will have been a waste of your time. So given that attribution errors are the only problem so critical that they can ruin your career in one deadly stroke, why do they even happen? How is it that any writer would devote less attention to citations than to any other aspect of their work? I really do think that in most cases it’s ignorance, and sometimes it’s apathy. The Crowley coverage can help. Both CNN and Politico offer side-by-side comparisons of Crowley’s plagiarized content and the sources it came from. Crowley wrote her dissertation before plagiarism detection software had become commonly available and widely used, so she might not have expected the paper would ever be scrutinized in quite this way (though it doesn’t explain her plagiarism in the 2012 book). Learning from Crowley's Example I: Mixing Correct and Incorrect AttributionThe comparison and comments in the Caton and Watkins piece show that her efforts at attribution are there, sort of, but are accompanied — sometimes in the same paragraph — by something improperly used or cited. Here’s an example: She had the presence of mind to quote the last part of the paragraph correctly, but it’s unclear why she wouldn’t have done so with the other thirty-seven words in this section. When I discover that a client has done something similar (which isn’t often because I only check text if it waves a red flag, and my only tool available is Google), I try to give them the benefit of the doubt. If you’ve ever committed this error or didn't realize there would be a problem with it, here’s my advice:

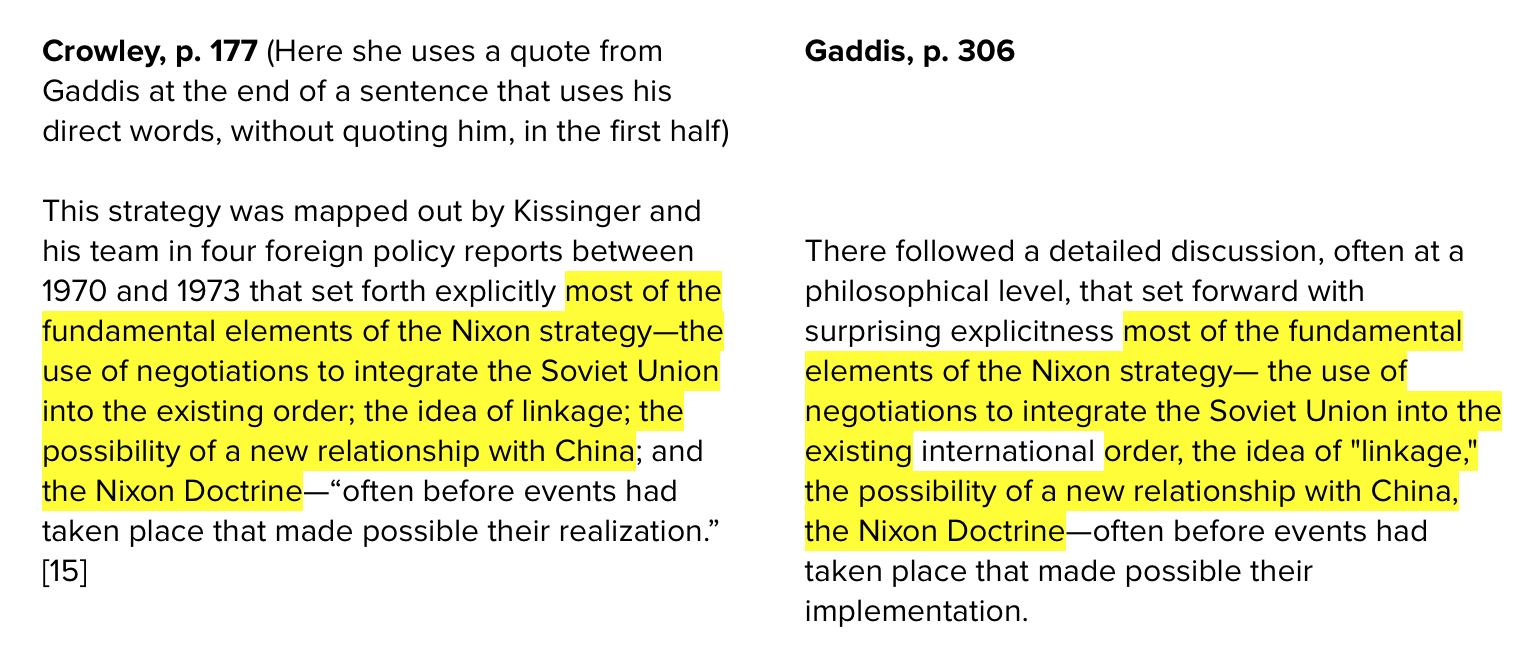

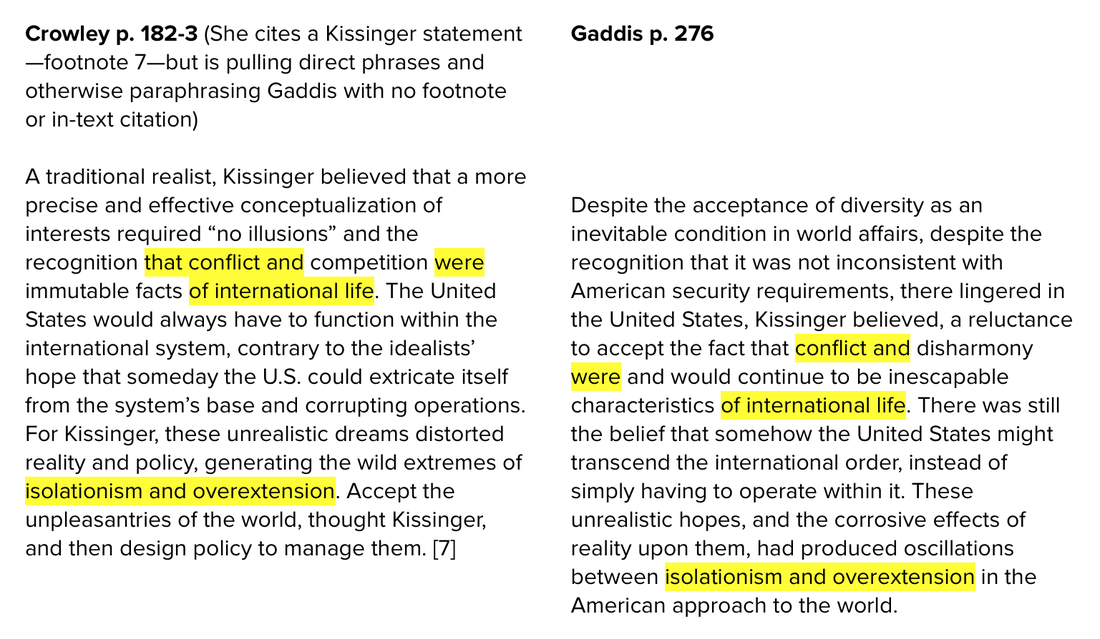

Learning from Crowley's Example II: The Perpetual Paraphrasing Problem and Word Count LogicTwo murky areas have to do with paraphrasing — when it's acceptable and when it's a problem — and the question of how much text from another source needs to be there before you have to put quotation marks around it. Back when I was teaching, students told me things like, “My high school English teacher said if it’s five words or more, it should be in quotes,” though it never seemed as though any two English teachers gave their students the same number of words. Let’s take a look at another excerpt from Crowley’s dissertation. The journalists appear to be using a computerized plagiarism checker, and computer programs don’t understand context, so three copied words in a row may or may not mean anything shady. But they call attention to the paragraphs, and it’s worth looking at their entire content, not just the parts that are highlighted. Many of the parts that are not identical are nonetheless simply swapped out — some with direct paraphrases and others with original phrases that nonetheless do little or nothing to alter the sentence structure. “Disharmony” became “competition,” “inescapable characteristics” became “immutable facts,” “unrealistic hopes” became “unrealistic dreams,” and “oscillations” became “wild extremes.” Meanwhile, “transcend the international order” became “extricate itself from the system’s base” while exchanging position with “having to operate within it” and “function within the international system.” There are two things to look at in the way Crowley treated her source material here that students and other writers should take to heart.

How Editors Can and Cannot Help with Citations and Attributiontl;dr: Editors can often help with citation formatting, but they aren't plagiarism detectors. Full explanation: In most cases, working with an editor on citations really just means the citations: formatting them and making sure they’re complete. You need to be aware of the policies that exist at the institutional, departmental, and program levels and your advisor’s requirements, along with what you and the editor agree that you will pay her for. Under normal circumstances, the editor will assume that all your quotes have quotation marks around them or are (or should be) put in block form. If you know you’re weak in any of those areas, you can communicate with your editor to figure out a way to highlight spots you need help formatting. In other words, you’re not trying to hide any quotes or passages that might not be presented correctly or hope they go unnoticed — you’re explicitly identifying them and asking for help with them. Those are the types of questions and considerations that apply to a “normal” paper with “normal” citation problems. With respect to more significant attribution errors, the main point that needs to be underlined is this: No one has responsibility for making sure your sources are correctly quoted and attributed but you. Your editor might spot problems, call them to your attention, and give you pointers for how to avoid the same mistakes in future drafts or chapters — but they also might not. Editors, like professors, are skilled readers who can sometimes see the variations in tone or voice that crop up in student papers and that raise red flags that some of the text might not be original to the student. But some of those variations are much more visible than others, and if the red flags don’t go up, editors aren’t going to intuitively know that you’ve done an oopsie with your attribution. Furthermore, even if they do locate and fix or query an oopsie — or seven, eight, twenty oopsies — it does not imply they will have found all of them. You, in such a case, need to learn from the comments the editor leaves concerning the found oopsies to correct the ones they didn’t spot. And to not make those mistakes again. Let’s say, for instance, you’re Monica Crowley, and you’ve hired a copyeditor who just happens to have just read one of the books you’ve used as a source. Let’s say this copyeditor recognizes the passages and leaves queries to you, saying, for instance, “Since I have the Christensen book on hand, I checked this passage against p. 248 and found that it’s a direct quote. I’ve enclosed this section of text in quotation marks and updated the footnote. Please do the same wherever else necessary.” The copyeditor has not read Gaddis, Larson, Oye, Milner, and the other authors you (Imaginary Crowley) have plagiarized and obviously hasn't memorized the entire Christensen book, either, so they haven’t made equivalent fixes or even queries. This doesn’t somehow mean that this one Christensen quote is the only one you shouldn’t plagiarize, and it doesn’t mean the editor has failed in their ability to spot problems. Rather, the fact that the copyeditor found even one instance is lucky for Imaginary Crowley because it means she should now know what else it’s necessary to go back to and fix. Crowley and other dissertation writers can’t rely on even that one fix happening. If it does, the writer should think of it as a bonus. Plagiarism of these kinds and others might get by the editor, and it might get by the committee. But if the dissertation gets pushed through plagiarism detection software, whether right away or 16 years down the line, it could mean the end of a career, or at least of all professional credibility. And all because a couple of quotation marks were just too much to type. ReferencesCaton, Alex, and Grace Watkins. 2017. "Trump Pick Monica Crowley Plagiarized Parts of her Ph.D. Dissertation." Politico, 9 January. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/01/monica-crowley-plagiarism-phd-dissertation-columbia-214612.

Kaczynski, Andrew, Chris Massie, and Nathan McDermott. 2017. "Trump Aide Monica Crowley Plagiarized Thousands of Words in Ph.D. Dissertation." CNN Money, 12 January. http://money.cnn.com/interactive/news/kfile-monica-crowley-dissertation-plagiarism/index.html.

5 Comments

1/18/2017 4 Comments New Year's OverresolutionsI have a confession to make. It shouldn’t be a confession, since it’s actually a positive thing, but so many people hate New Year’s resolutions that I feel a little guilty about it. It’s simply this: I love making them, and they (sometimes) work for me. There, I said it. Some of the reasons I love editing are the reasons I love the New Year: the blank slate; the opportunity to apply completion, pattern, and consistency; the order and organization of a resolution held. And so I thought I’d share my resolution habits, in case they help anyone — not just for resolutions (it’s a couple weeks late or eleven months early for that anyway) but for any other applications they might have. Although I’ve always loved the idea of the resolution, I wasn’t always successful at it, for the same reasons others shun it. It takes self-discipline to start a good habit or stop a bad one, and most resolutions are for things you don’t truly want to be doing; you resolve it because you know you should. It took many years of fiddling with the formula before I found a way to make it work for me (and to figure out why sometimes it already had). The key was overresolving. This isn’t the same as setting overly ambitious resolutions, but setting all the resolutions I wanted. Now, there are a couple of other guidelines I follow that you’ve heard before, over and over, in every list of ways to be productive ever. The fact that they’re cliché also means they’re time-proven and necessary. The first is making sure your goals are concrete (that is, “Write half an hour every day” rather than “Write more”). The second is making sure to set both shoft-term and long-term benchmarks (such as the writing example for the short term and “Complete a novel by the end of the year” for the long term). I won’t go any more deeply into those because plenty of other people already have. Let’s get straight to the weirder one. I’ve always been ambitious with my resolutions — I’ll usually write down a dozen or so on the last day of the year. But my practice of overresolving-as-strategy dates back to one year when, after doing so, I managed to fulfill every single “Do ________ every day” goal I had set for myself on January 1. I’d gotten up bright and early, met my work target, exercised, cooked, cleaned, read, written trivia, and even practiced the guitar that usually gathers dust in the corner. Everything I wanted to spend every day of the coming year doing, I did. I went to bed with a tremendous sense of accomplishment along with the potent awareness that I was absolutely insane. It was, after all, 2 in the morning; it had taken me 19 hours to do all that. It had never been so clear how much I’d overresolved before because I’d never managed to accomplish everything I’d planned. Instead, I’d finish the day thinking I’d failed at half my resolutions yet again. With the new realization that complete success on these terms was genuinely ludicrous, I began to develop a different definition of failure and success. Over the coming days and weeks, I allowed myself to be a bit more flexible with some of the things I was trying to do. I let most of my resolutions fall away or become much less stringent until I was left with a few I was managing to stick with. The guitar went back to gathering dust, and daily cooking was demoted to twice a week. I let the resolutions tell me which among them I would do 365 days out of 365. When the rest were pared away, I ended up with three completely manageable goals: scooping the litter box every morning, washing all the dishes every night, and maintaining an organized client and project spreadsheet. I kept these all year, and they’ve become enough of a habit that I no longer need to resolve to do them — I just do. The main and obvious question, I realize, is probably Why don’t I just make fewer resolutions in the first place? And I certainly could do that, but what overresolving does, when accompanied by a comfortable paring-down, is let me figure out which ones the sticking resolutions are going to be. If I only made three, and I discovered I couldn’t keep any of them — because those weren’t the resolutions that my current life circumstances had room for — then I’d be left without any improvement in my habits. But setting twelve and then keeping three, without knowing ahead of time which three they’re going to be, allows me to discover my successes. So would this strategy work for anyone else? I honestly have no idea. If you aren’t already one to see the new year as a blank slate and an opportunity for change, then this won’t alter that. But if your brain works as oddly as mine does, and you’re someone who wants to make and keep resolutions but haven’t been able to, then maybe it would be worth a try. I can think of a couple of ways this topic can apply to other situations, though. For instance, if you tend to have a concrete perception of failure and success, it helps to remember that those perceptions aren’t always set in stone. It depends on context, of course, but not all failures are truly objective, and viewing small setbacks as part of the process of success is more often an option than it’s sometimes easy to think. For example, if you’re applying to jobs, it can be easy to feel let down by each and every one that turns you down or that you never even hear from. If you define success more broadly and see the declined jobs not as failures but as steps to the eventual offer, they shouldn’t be as disheartening. Another application is in learning to build flexibility into your goals, projects, plans, processes, and so on. If, for example, you’re writing a dissertation, you may need to stick to a standard intro/lit review/three chapters/conclusion structure or whatever variation on it your advisor prefers. You might even start with a tightly structured outline for every chapter. But that doesn’t mean you need to stick to it if your material is pulling you in a different direction. Writing a dissertation can be a fragile process, and getting the words on the page is more important than having them in the correct order when you write them. As an example of how this applies elsewhere, I see this principle coming in handy when I’m doing my volunteer tech support in Second Life. A lot of the time, people have an idea of what they want their computer to do, and they’re absolutely certain it should do it. They don’t take the time to listen to what the computer is telling them about its capacity to perform. It’s worthwhile to pay attention to your graphics card, to your resolutions, to your dissertation. They may be inanimate objects and abstract concepts, but thinking of them as “communicating” their needs with you is a helpful way to see when you’re applying force where adaptation would be more productive. While I certainly have a lot of room for improvement in the area of productivity myself, I can certainly add my two cents to this pepetually useful topic. The most important strategy is whatever you find works for you. If the strategy of overresolution fits in your bag of tricks as it does mine, then I’m happy to have given it to you. 9/8/2016 5 Comments Hiring a Dissertation Editor: A Guide for Doctoral Candidates. Part 3, Chapter-by-Chapter vs. Full DraftAnother popular request from dissertation clients tends to be if they can send their work chapter-by-chapter instead of in one complete draft. The dissertation writing process is very compartmentalized, so it’s normal for you to be thinking of it within that structure, but the editing process is often different, and there are some advantages to shifting to a full-draft perspective when the time comes. Some editors will be perfectly fine with separate chapters, while others will prefer to receive the document in one piece. Style editing. When copyeditors edit, they’re often making a list (called a style sheet) of universal changes they’re making in order to make sure they’re making the consistent choice throughout the document. It’s not unusual for a style choice made at the beginning of a lengthy document to prove problematic by the end. If they have the whole document in front of them, they can make the late change relatively easily to the earlier chapters. If they’ve already returned those chapters, then they’re forced to stick with the less-than-ideal style option. Say, for instance, there is a term you use both hyphenated and unhyphenated in the first chapter. The editor will pick one of those variants (for example, the hyphenated one) and make all instances consistent. Then she might receive your later chapters and discover that by the time you wrote those, you became more consistent with your own usage and used the unhyphenated version of the same term. If the editor had the entire draft from the beginning, she would have had a broader perspective on your use and chosen the unhyphenated variant. Formatting. In addition to APA formatting, which some departments require, graduate schools have very specific requirements for dissertations that include pagination, margins, organization of front matter and back matter, placement of tables and figures, and sometimes headings, fonts, and other details. Much of it can be accomplished more easily with a complete draft at hand. Citations. One of the things an editor can do is cross-check your references with their inclusion in your reference list and vice-versa. This task requires both the reference list and the chapters be present. Although this can be done chapter-by-chapter, as well, it will be a speedier and easier process (and thus cheaper for you) if the editor has everything in one place. All of the above are aspects of the editing process that can be done more easily and more speedily with a full draft than individual chapters. It’s not always a huge difference, but across 200 or 300 pages, it can add up. While many editors may be open to working chapter-by-chapter, the difference in the process is likely to affect you at the pocketbook end. Is Chapter-by-Chapter Ever Better?If you don’t expect to be finished writing the entire dissertation until a week or two before it’s due, then your editor would probably rather work on the chapters you’ve completed than wait until the last minute to have the full draft. But again, this is a matter of preference, and it’s best to confer with them early on this. Some might want the entire draft early and fully.

8/9/2016 5 Comments Hiring a Dissertation Editor: A Guide for Doctoral Candidates. Part 2, Setting a TimelineThe biggest mistake dissertation writers make — and they make it a lot — is expecting editing to be performed too early in the process.

Incidentally, the biggest mistake I have made — and I have made it a lot myself — is accepting chapters for editing too early in the process. In any type of publishing, the sequence of editing is supposed to go from in-depth editing to surface editing. Deep to shallow. That is, substantive or developmental editing (the kind that involves changes to ideas and their organization, research and its presentation, and so on) is performed on the rough draft. After that rough draft is revised, copyediting can take place, and then finally proofreading. In a dissertation scheme, the people who perform the substantive editing are you and your advisor. The person who performs the copyediting and proofreading is your editor (and perhaps a separate proofreader). This means that ideally, your editor should not be receiving your draft until you are done with any and all research, writing, and revising you are planning to do. Where the mistake comes in is that dissertation writers often — very often — want the editor to go over their draft before their supervisor or advisor has seen and commented on it. I can understand wanting to put your best foot forward immediately and not wanting your advisor to have to work with something rough and unfinished. However, there will nearly always be revisions to make after your advisor has read this draft, and those revisions are often substantial. If you ask your editor to then edit the material again after you’ve made those revisions, she may be performing an entirely new job. This isn’t the way editing normally works, and it will be within her right and prerogative to charge you twice for a timeline like this — once for the prerevision draft and once for the postrevision draft. If the editor is working at an hourly rate, then you can imagine how fees will mount with each draft. To keep costs for yourself to a minimum, plan your dissertation timeline far enough in advance so that it looks something like this: (1) Write your chapters and submit each one in rough form to your advisor/supervisor. (2) Your advisor/supervisor comments on these drafts and requests revisions. (3a) Repeat 1 and 2 until your advisor has no more suggestions that will involve reorganizing material, rewriting material, or adding new paragraphs. (3b) While you’re in the process of writing and revising, search for and contact an editor, confirm their availability, and find out how much time they will need for editing a full dissertation. (4) After your substantive revisions are complete, send the entire dissertation to your editor with a sufficient amount of time to work before you need to submit the work for defense. Editors vary widely in how much time they need, but expect as a minimum one week per chapter or one full month for a completed dissertation draft. This is the minimum I work with. Some editors work much faster than I do, but expect to pay more for fast turnarounds. Editors might also have many projects on their plates and need a longer turnaround. Be in communication before you need them. 8/3/2016 5 Comments Hiring a Dissertation Editor: A Guide for Doctoral Candidates. Part 1, Finding and Contacting an EditorIf you are a doctoral candidate who has been asked, encouraged, or maybe even required to hire an editor to help with your dissertation—whether for text editing, citation styling, or document formatting—you might feel a bit at sea. The purpose of this series of posts is to help you find an editor and to know what to expect throughout the process of working with one. Finding an EditorWord of mouth. If your advisor or your department has editors’ names on hand, that can be the best way to go. They will most likely be recommending editors who are somewhat familiar with your field of research or with the norms of your department or university. You can also ask if any prior PhD candidates in your department or program have hired an editor and see if you can get their name(s). Directories. If you have no word-of-mouth channels for an editor, however, you can still find many if you know which directories to look in and if you have a bit of time to put toward inquiring into their availability. The Editorial Freelancers Association (EFA) has a directory you can search by location, skills, or specialties. Under Skills, you’re most likely looking for a proofreader or “editor, copy,” unless your advisor has told you otherwise. Under Specialities, make sure to select “scholarly.” Some academic fields are specified in the list, as well, but when it comes to editing, you may not need to limit yourself too narrowly in that respect. There is also a directory of copyediting freelancers maintained by CE-L, a mailing list for editing professionals. When you visit this one, make sure to click the Freelancers heading—there is no separate link to that tab—and you’ll find a long alphabetical list of freelance editors. This directory doesn’t have a search function, but you can use your web browser’s Find ability to locate terms that might be used in the freelancers’ listings. Contacting an EditorYou might obtain an email address, a website, or both from your word-of-mouth or directory search. Or you might get a phone number or social media account such as LinkedIn or Facebook. Freelancers’ websites will often have submission or contact forms, or they might provide any of the other above means of communication. I’ll focus on email because it is, in my experience, the most common mode of communication in this business, but the guidelines will apply to first contact through any of these other methods as well.

The two most important pieces of info. When you initiate contact with a freelancer, there is some info they’ll need from you as well as info you’ll want to obtain from them. The main concern to address before anything else is availability. If the freelancer isn’t available at the time you need them for the amount of work you need them to do, then it’s good to know that first thing. And so whatever else your initial email says or asks, it will be most helpful to mention:

Other questions the editor might have for you include what type of material it is, what type of editing you’re looking for (e.g., text editing, dissertation formatting, citation styling), or whether you want editing of early chapters, a pre-defense draft, or the post-defense revision. Questions you might have for the editor, meanwhile, include how they price (e.g., flat rate or hourly); their editing process, such as number of editing rounds their fee covers; their experience in your citation style; or their background in editing dissertations in general or in your field in particular (here I mean “field” in the broad sense; see my previous post In Praise of Inexpertise for a discussion of whether experience in your subject matter is likely to be important or not). Further posts on this topic will cover setting a timeline, understanding what to expect of a dissertation editor, and how to keep excess costs down by planning ahead and communicating early and often. * You may be tempted to provide a page count, and some editors might ask for that, but bear in mind that in the editing world, a “page” is defined as a segment of 250 words, so an accurate page count is one that is based on word count anyway. If you provide a page count, do so by dividing your word count by 250, rather than by giving how many 8.5x11-inch “pages” in your Word document contain material. Sometimes we get guidelines of writing stuck so firmly in our heads that we become convinced they’re rules of grammar that “everyone” knows are entirely factual. Often, they are guidelines we learned at a young age, leading us to pronounce, “This is 8th-grade grammar!” if someone questions us about it. The difficulty with 8th-grade grammar is that middle school teachers may be teaching not only widely accepted rules but also guidelines for subjectively understood “good” writing. And whether it’s because the students are thirteen years old, because we don’t remember every piece of our lessons years later, or because not all teachers make it fully clear, the distinction doesn’t always stick. The topics I covered in my “seldoms” series (paragraph-ending quotations, sentence-opening conjunctions, and passive voice) have an element of that in them, but they pop up all the time, so that one person’s malleable style preference is another person’s hard-and-fast rule. Another example is introducing quotations with the word “that.” This is a convention that comes up more often in scholarly nonfiction than it does in other writing genres, and it’s fairly rare in fiction. Since I’m so accustomed to it, I didn’t realize until it came up in a social media discussion recently that some people think it’s wrong. Here’s what I’m referring to: With another aphorism he reminded his readers that “experience keeps a dear school, but fools will learn in no other”—an observation as true today as then. Both of these examples come from the Chicago Manual of Style, in a section (13.14) that is not on the topical word, “that,” but on capitalization. It’s a way of presenting a quotation while suiting the syntax of the sentence around it to its use, and it’s so standard in this style of writing that it doesn’t even merit mention. Yet when this construction was raised (also in a discussion on capitalization, interestingly), three separate people insisted that what follows the word “that” is implied to be paraphrase and can’t (they actually said can’t, not shouldn’t) be a direct quote.

It wasn’t until I provided the above examples from Chicago that the arguments ebbed. Since I hadn’t heard this “rule” about not introducing a quote with the word “that” before this conversation, I can’t be certain where it comes from, but my best guess is that it’s an example of mistaking style for grammar. I can in fact see arguments for avoiding it for style reasons, not grammatical ones. Going with the comma instead of that is arguably more concise, for instance, and it’s a construction with few uses in a fiction context. However, these points don’t make the that construction grammatically wrong, and there are times when it works very well. As I noted, it’s very common in scholarly writing, so I would assume (or hope) that the naysayers focus on other genres in their editing and were for that reason unfamiliar with its acceptability. This particular topic is merely an example of a general tendency most of us (“us” being word lovers) have at some point to confuse style choices with rules of grammar or mechanics. This one was only notable to me because I had never heard the argument made before three individuals made it, despite the appearance of counter-examples in a reference that one of them claimed to adhere to. We come across them all the time, with some “rules” (e.g., splitting infinitives, ending sentences with prepositions) evoking far more discussion about how they’re no longer rules than discussion of toeing the line on them. As editors, we regularly mix enforcement of widely accepted rules with application of style choices so fluidly that we don’t always think about which is which, and with some clients in some types of editing, it doesn’t matter. It’s good to be aware where on the style–rule spectrum all our changes fall, though, and how that place on the spectrum might even vary with different genres, media, or audiences. It serves us and our clients well both in our work and in our debates among ourselves. 5/17/2016 6 Comments Changes You Can Make to QuotationsLet’s say you’re always good about citing your sources, checking that you didn’t introduce typos into your quoted material, and marking any changes to the original with clear indicators like ellipsis points and brackets, with an appropriately placed “[sic]” where you made a point not to change it. These are all good things to be aware of. But there are a handful of changes you can make to quotations that actually shouldn’t be bracketed if you’re using APA or Chicago style.* If you have either manual in front of you, we’ll be working with APA section 6.07 and Chicago section 13.7. There are three types of changes that both manuals allow you to change without indication. The Case of the First Letter in a QuotationThat heading sounds like a very library-centric Nancy Drew mystery, but we’re just talking about lowercase and uppercase letters. Many conscientious scholars have noticed this treatment of a quotation in a book or article and thoughtfully applied it to their own work: Original: He had little schooling, and he describes his early surroundings as poor and mean.† In the original, the word “he” was capitalized, and the author quoting it is being careful enough to indicate their change. There are styles that require that the h be bracketed in this case, but neither Chicago nor APA is among them. In the APA’s words, “The first letter of the first word in a quotation may be changed to an uppercase or a lowercase letter.” So if you’re following either of these styles, you should really write: Correct for APA/Chicago: Most modern readers might be surprised that “he had little schooling, and he describes his early surroundings as poor and mean.” Quotation Marks within a QuotationThe quotation marks that appear in a text may be double (“/”) or single (‘/’) depending on the style the original author was following, on whether the quotation itself is within a quotation, and in some cases whether the text is quoted material or words being presented “as words.” When you quote material including quotation marks, you might need to switch from single to double or vice versa. Both APA and Chicago allow this change without any indication that you did it. Here’s an example: Original: Lyra said, “Ah! Marchpane!” and settled back comfortably to hear what happened next.‡ The dialogue was enclosed within double quotation marks in the original, so they appear in single quotation marks in the quoted version, within double quotation marks that surround the entire quoted sentence. The bracketed s indicates a letter changed from the original. That is a type of quotation change you need to make clear. The Punctuation Mark at the End of the QuotationThis punctuation mark should suit your text’s syntax, which may or may not be that used in the original. Original: So we have to start small, by thinking through what is needed for a new gender ideology for everyone and for new types of relationships for African Amerian women and men based on these fresh ways of seeing others and ourselves. Forging our own original paths might enable us to develop a progressive Black sexual politics that one day will meet the challenge of HIV/AIDS.§ Note that Collins’s sentence ends after “HIV/AIDS,” but mine doesn’t. So while she follows the abbreviations with a period, I follow them with a comma to suit my context. That change doesn’t need to be given brackets or any other kind of identifying marks. Next, I made the opposite change: whereas “women and men” appears unpunctuated in the middle of a sentence for her, it’s at the end of the sentence in mine and thus gets a period, also unbracketed. And yes, the comma and the period both go within the quotation marks, as they always do in APA and Chicago styles, regardless of what the text is. The rules are a little different for other punctuation marks (e.g., semicolons, question marks, parentheses), but those are beyond the scope of this post. Additional Changes Specific to Chicago StyleThe three above are the only changes APA allows to be implemented without indication, but Chicago has a few more.

So use your best judgment:

* Chicago Manual of Style (16th ed.) or American Psychological Association (6th ed.). These are the two books my particular work niche has me use most often, and if you’re in the humanities or social sciences, chances are good you need to use one or both of these too. † Charles W. Eliot, introductory note to The Pilgrim’s Progress, by John Bunyan, The Harvard Classics, Vol. 15 (New York: P. F. Collier & Son, 1909), 3. ‡ Philip Pullman, The Amber Spyglass (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 447. § Patricia Hill Collins, Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism (New York: Routledge, 2004), 301. You’re at the end of your dissertation project, and all you have left to write is that often-optional section that goes in the front matter, called Acknowledgments (or Acknowledgements in British and Australian English). This might be slightly intimidating because you’ve probably never written such a section before and you’re not really sure how it goes, but you can relax. Your degree doesn’t hang in the balance for this, and it doesn’t usually need to be OKed by anyone (though it should be proofread). It can be as short or as long as you want it to be, as terse or as flowery, and written in the first person. Here’s a checklist of people you can, should, or in some cases must include in your Acknowledgments. Not all of these apply to everyone, and it’s nonexhaustive, intended only to get you started and to remind you of a few key folks you might otherwise have forgotten. Use your best judgment and consider who you couldn’t have completed this process without, whose help made it what it is, and who eased the way for you. People who gave you hands-on or participatory assistance:Your advisor and other committee members. It would be a real faux-pas to forget anyone in this group. Your advisor probably has almost as much emotional investment in your work as you have by the time it’s complete, and your committee on the whole is the reason you’re getting this degree. Study participants. You don’t have to thank amoebas, but if you performed research with living human participants—in interviews, surveys, participant observation, or any other method—it’s courteous to acknowledge them. You’re not thanking them by name unless their names were used in the dissertation (e.g., experts who were interviewed for their expertise), but a blanket thank-you to the group of them will be a nice professional touch. You couldn’t have done this research without them. Coresearchers. Although you’re writing your dissertation on your own, you might have had coresearchers who worked with you on data collection and the like. Don’t forget to thank them! Your editor and/or proofreader(s), whether paid or unpaid. Although I admit I love seeing my name in an Acknowledgments section, that’s not the main reason I include the category I belong to in this discussion. At best, it comes a distant third to etiquette and ethics. With respect to professional etiquette, it’s possible that your editor will have spent more time interacting with your dissertation than anyone but you, and depending on how heavy the edit was, that includes your advisor too. You don’t want to slight someone who spent 60 hours or more on this document. Take a look at any published book on your shelves and see how many published authors do and don’t thank their editors. The primary reason editors and proofreaders are included, though, is ethics. It is critical to be transparent about how much outside assistance you received on the content of a document you’re submitting for academic credit. Editors Canada recommends that editors include a requirement in their contracts or agreement forms that the thesis/dissertation author acknowledge the editor, and these days I do. Some graduate schools require the dissertation author to do so as well. The last thing you want is for committee members or outside readers to suspect you of hiding assistance of this kind. People who contributed content-related assistance:Funders. If you received grants of any kind for completing your research, even if it was not for travel or equipment but merely to allow you to work less or not at all during the process, your funding sources deserve an acknowledgment here. Permission holders. If you reproduced previously copyrighted materials, you’d have had to request permission from the copyright holders to do so. Even if you included them in your (properly formatted APA-style) figure captions, it’s nice — and at some universities required — to thank them here as well. Transcriptionists and typists. People who performed professional services for you deserve a place in your acknowledgments. Think about how much time they saved you when they did this work and you didn’t have to. People who provided other kinds of direct assistance:Librarians. University librarians can be invaluable resources for helping you find exactly the kind of research material you need. Although a large chunk of research can be done online with electronic journals, and your library might even deliver the books you check out to your department office, it can still be worthwhile to visit the actual library in actual person and get help from an actual librarian. And if you do, it costs you nothing and will be deeply appreciated if you include a line acknowledging those who helped you. Office staff. If they helped you make sense of the dates you had to turn things in or fulfill requirements, found you the forms you needed, scheduled your defense, helped you replace the toner, sent you reminders, or anything else that made it just that little bit easier to get things done, they may deserve a call-out. Student assistants. Most doctoral candidates aren’t lucky enough to have work-study assistants of their own, but it’s not completely unknown. If you were one of the fortunate few, these little sprouts might just pee their pants to see their names on your Acknowledgments page — if their assistance helped you get your dissertation finished, of course. People who provided emotional support:Family and partners. If you live with them, then they have suffered along with you and probably in their own independent ways as well. If you don’t live with them, parents in particular likely contributed something emotional, financial, or hands-on to the fact that you’ve reached this point in your work.

Friends. It’s nice to include any who have offered the types of support listed above for you. This isn’t the time to go all Golden Girls (“Thank you for being a friend . . .”) but to acknowledge those who had a direct and positive impact on the writing of the dissertation. Spiritual personae. It’s very common for people of faith to include anyone, heavenly or earthbound, who provided spiritual strength and guidance to them throughout the dissertation process. This doesn’t mean you must thank a pastor, rabbi, priest, imam, and so on just because you have one, but if they made the work easier in some way, they might be candidates for acknowledgment. If you've made it this far in your dissertation to need this post, congratulations! You're almost there! Have I left any out? Underemphasized anyone's importance? What's your experience with remembering everyone you meant to acknowledge? 2/17/2016 4 Comments Leaving it on the TableWhen should you use tables to supplement your writing and when is it unnecessary? Creation of tables in Word or Excel has a learning curve, so if you struggle with it at first as a writer or editor, you’re not alone.

The first thing everyone should know is the terminology applying to this topic. If you get that down, you’ll be better able to look up help for problems if they occur, not to mention being able to communicate with your editor, advisor, and others in the process, as well as not signaling to the reader that you’re uninformed. Table: A table is a grid-style presentation of alphanumeric data (that is, letters, words, and numbers) in rows and columns.* If you use APA style, be aware that it includes very specific formatting rules for tables and their captions. Chart or graph: Both of these words refer to a data display that presents the relationships among pieces of information in a visually helpful way. Bar charts, pie charts, flow charts, and line graphs are common types. Figure: The figure category can include charts or graphs (but not tables), as well as any other kind of visual material that enhances the text, such as illustrations or photographs. APA style, again, has particular rules for captioning figures. Book Review of A Sequence for Academic Writing (5th ed.), by Laurence Behrens and Leonard J. Rosen

[Please note: I read the fifth edition, but there is a sixth edition available.] I picked this book up while browsing in the language arts section of a local discount bookstore, hoping that it would give me some ideas for substantive feedback I could give on theses and other graduate student materials that come my way. It’s a text book meant to accompany a course on writing, probably targeting first- and second-year undergraduates, but students at any level who haven’t taken such a course can probably benefit from its instructional style. Laurence Behrens and Leonard Rosen begin by sketching out different ways of understanding and interpreting text in a chapter on “Summarizing, Paraphrasing, and Quoting,” anchoring this sequence on writing firmly in the process of reading. Academic writing is a form of conversation one has with one’s predecessors in the field, and this book is designed to help the student learn to formulate his or her side of that conversation. The skills of summary, paraphrase, and quotation sound basic, but if a student doesn’t have a good grasp on them early on, there may be problems with how he or she engages with and synthesizes research materials later on. I’ve covered topics in this blog that rely directly on developing these approaches. |

Archives

March 2017

CategoriesAuthorI'm Lea, a freelance editor who specializes in academic and nonfiction materials. More info about my services is available throughout this site. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed